Thaddeus Cahill

Although it may come as a surprise to many who regard the electronic organ as an invention of the 1930s, 2006 marks the instrument’s centenary: the first of its type was publicly unveiled at a concert in New York on 26 September 1906.

Instruments using electricity had been around since the invention of saucer bells struck through the agency of static electricity in the mid-eighteenth century. Organs with action systems powered by or incorporating electric mechanisms had existed since the 1830s, but this was the first public performance of an organ of which the sounds were generated purely electronically.

The Telharmonium could not be regarded as a commercial success, but in its principles it laid the groundwork for organs that could be successful once amplifiers and loudspeakers had been developed.

**********

Robert Hope-Jones was one of the first (if not the first) heralds of an organ that would contain no pipes, the sounds being generated electrically and formed “by combination of the various upper partials with the ground tone, each in differing degree”. This remarkable forecast was included in an address to the College of Organists entitled Electrical Aid to the Organist that he presented on 5 May 1891.

Bearing in mind the self-serving nature and questionable veracity of some sections of Hope-Jones’ address, it is not surprising that his startling forecast of an electronic instrument that would make the huge wind organ…ere long breath his last and …become… extinct has generally been regarded as a mere flight of fancy. This scepticism was perhaps reinforced by the fact that the pipeless organ appeared to exist only in the mind of RH-J himself. He had not converted his thoughts into hardware, as he claimed his time was fully occupied designing and building pipe organs and their control systems, and it appears to have continued so until his death in 1914.

The general concept of synthesis of tones through the addition of harmonic frequencies to fundamentals dated back to the 1860s, when Helmholtz was conducting experiments into the nature and composition of natural sounds, so this was not a figment of Hope-Jones’ imagination. It is quite within the bounds of possibility that he had, as he stated to the (not yet Royal) College of Organists , conducted some preliminary work in that field.

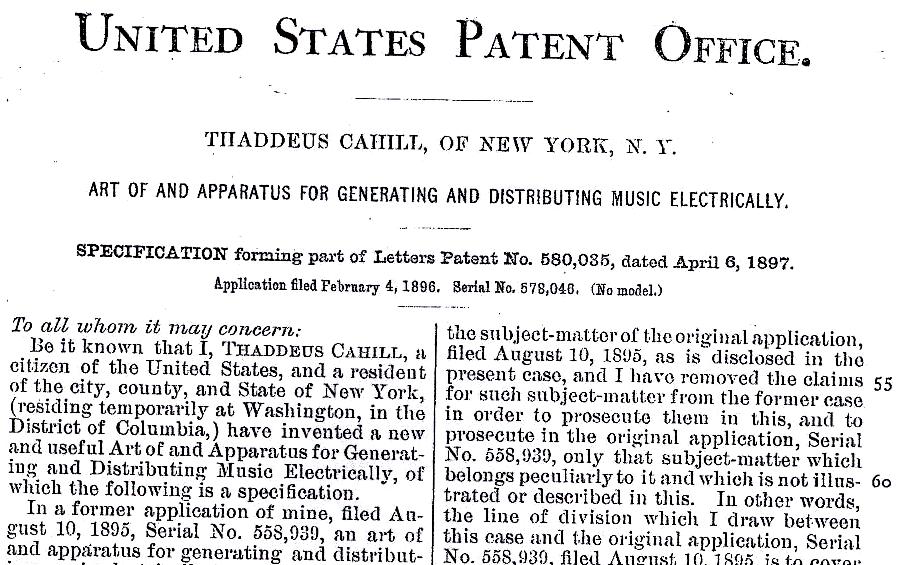

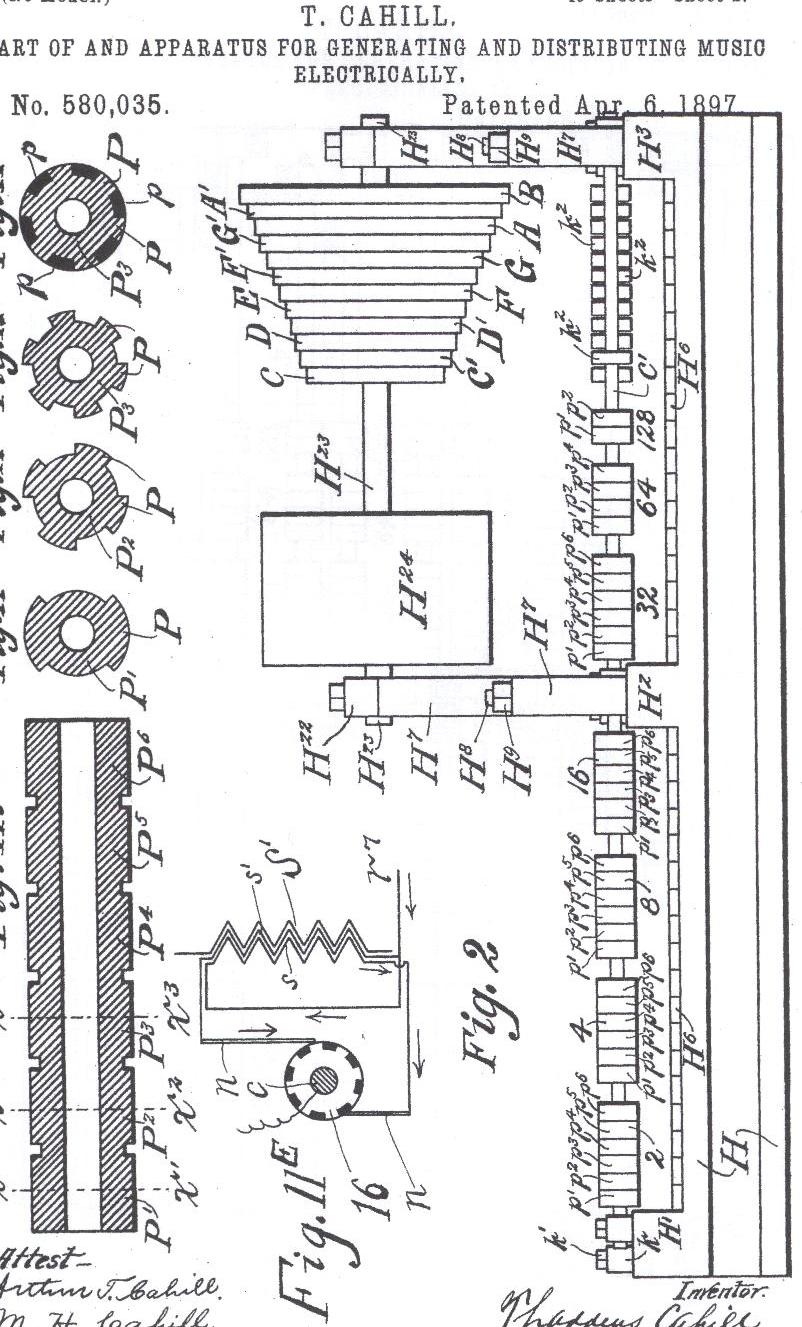

Within a couple of years of Hope-Jones’ claims, Thaddeus Cahill, an inventor in Washington DC had independently formulated practical ideas, and by 1895 had secured a set of patents, soon to be supplemented by a second set in 1897 for an Art of and Apparatus for Generating and Distributing Music Electrically. Construction of a prototype began in approximately 1898, and by 1901 a simplified instrument was complete.

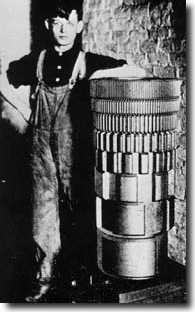

Cahill named his instrument the Telharmonium (it is sometimes alternatively referred to as “Teleharmonium” or “Dynamophone”). Its workings contained so-called rheotomes, which were large cylindrical drums around the circumference of which in bands were raised bumps that corresponded to a fundamental and a set of harmonic frequencies. Magnetic coils of wire close to the rotating cylinders had induced in them electricity, the frequency of which varied in pitch according to the number of bumps on the relevant band of bumps, the intensity varying as the coils were placed closer to or further away from the bumps (this was controlled by touch-sensitive keyboards) . Although the patent prescribed 408 rheotomes, the prototype had only 35, each of which had seven bands of bumps, creating seven octaves of the same note per rheotome. The whole instrument weighed a mere 7 tons. (Jay Williston, Thaddeus Cahill’s Teleharmonium, 2000, http://www.synthmuseum.com/magazine/0102jw.html)

Rheotome

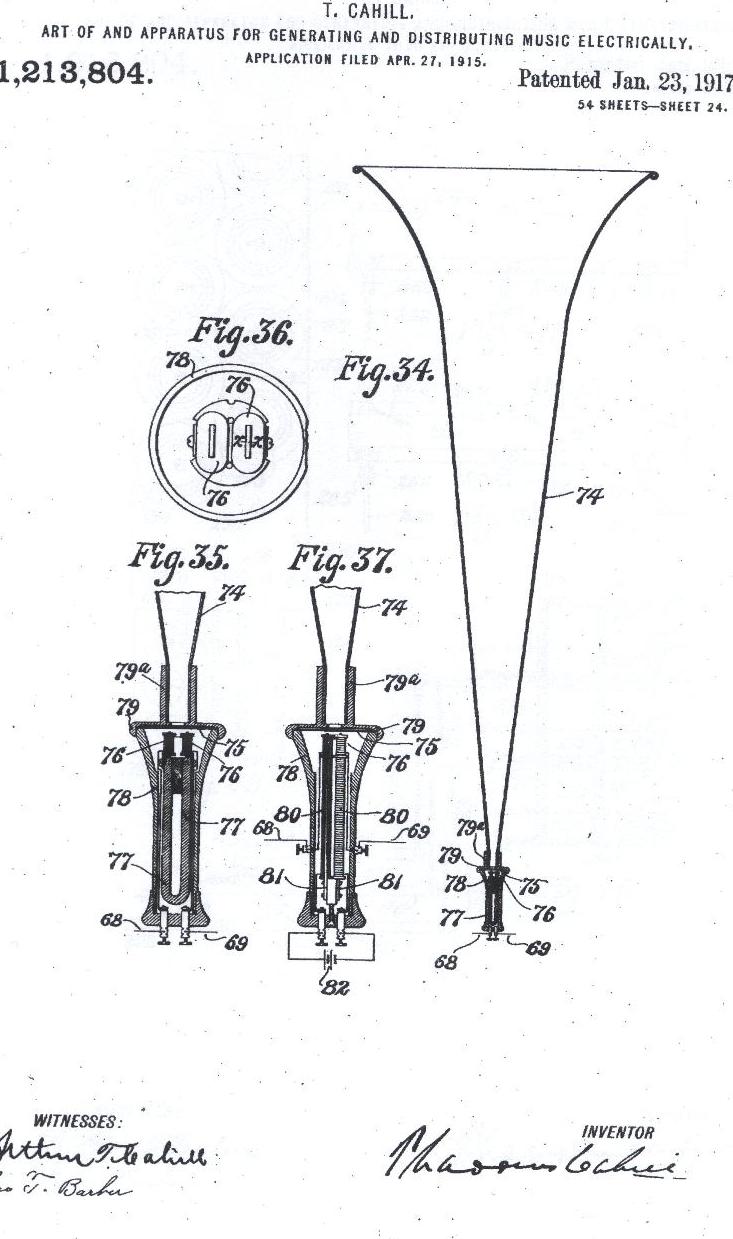

The general principle of the generation of note frequencies was very much that used some 30 years later in tone-wheel organs. Strange as it may seem, the major problem, and one that seemed almost insuperable, was not generating the frequencies, but enabling them to be heard. At this stage, amplifiers had yet to be invented, and even the triode valve had only just been invented by De Forest. There was no such thing as a loudspeaker. Like Hope-Jones, Cahill had a background in telephony, and he conceived the idea of using a telephone receiver fitted with a megaphone-like funnel, to convert through the magnetic diaphragm electrical frequencies into audible sounds. As will be readily apparent, the telephone receiver does not normally output a significant volume of sound, even with a funnel attached. It was thus necessary to generate very high power signals so that the sound could be heard without placing the receiver to the ear, and be made sufficient to fill a room.

Small though this demonstration prototype may have been in comparison to Cahill’s patent specifications, it attracted the interest, and, more importantly, the financial backing of those who heard it at the Maryland Club in Baltimore .

Cahill’s object was that his instrument would be located centrally and its generated sounds would be transmitted through the telephone network to both private and commercial subscribers. It was in many ways a pioneer variety of Muzak.

Heartened by the success of his demonstration in Baltimore , Cahill established the New England Electric Music Company in 1902 and started to build a full-size Telharmonium in a warehouse in Holyoke , Massachusetts .

As construction continued during the next four years some experimental performances on the Telharmonium were “broadcast” from the factory to the Hotel Hamilton.

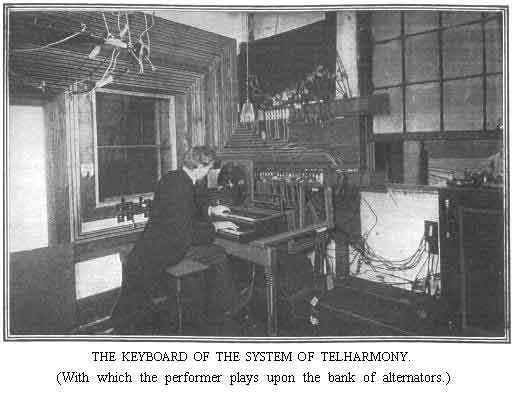

It is perhaps not surprising that such an esoteric instrument in its larger version did not just have the usual twelve notes per octave. The Telharmonium had thirty-six, and thus was not only capable of realising previously unknown enharmonic subtleties, but was thereby also made incredibly difficult to play; reports of performances indicate that players did not always completely overcome the difficulties inherent in performing on keyboards with three times the normal number of notes per octave. Most times the instruments seem to have been played by two or more players, two to control the bass and treble, respectively, and on occasion a third to assist with registration control.

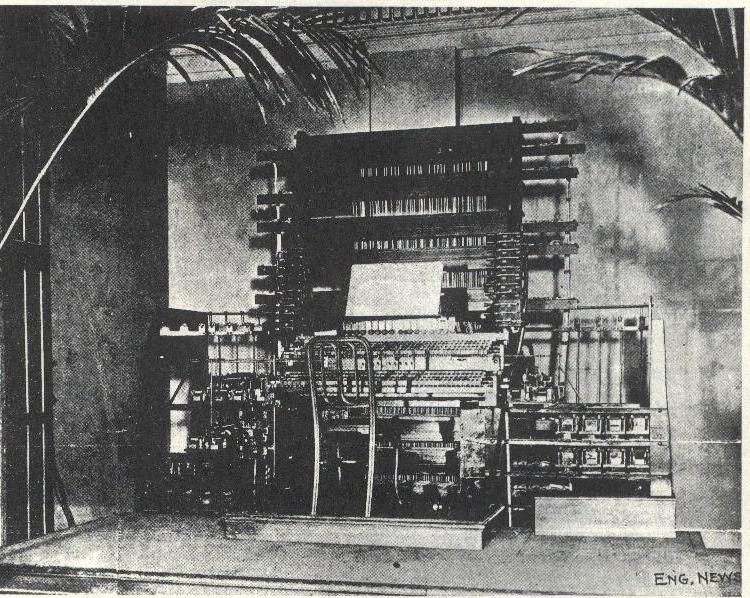

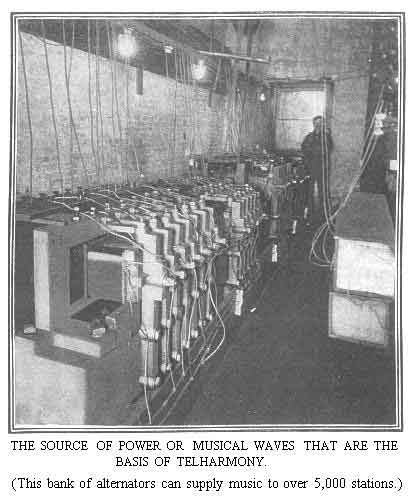

By 1906, the second Telharmonium was ready. This instrument had 145 gear driven alternators of an improved type over the original rheotomes. There were some 2000 electric switches at the console, and the instrument could produce frequencies in the range 40-4000Hz, which was perhaps a little optimistic in view of the limited frequency response of the diaphragm-driven telephone receivers that actually emitted the final sounds.

This instrument is referred to in some writings as “portable”. This does seem to place on that word a burden of meaning somewhat beyond its commonly-understood definition. The main sound-generating and tonal adjustment components extended some 60 feet. Overall, it weighed around 200 tons, and had cost $200,000 to construct. It was indeed “portable” – provided you had handy thirty or so railway box cars, which is what it took to transport it to New York City for its public unveiling. It is well described in two contemporary journal articles:

The Cahill Telharmonium may be compared with a pipe organ. The performer at its keyboard, instead of playing upon air in the pipes, plays upon the electric current that is being generated in a large number of small dynamo-electric machines of the "alternating-current" type. These little "inductor" alternators are of quite simple construction, from the mechanical standpoint, though it is needless to say that the inventor did not find out at once all he wanted to know about them. That took a good ten years. In each alternator the current surges to and fro at a different frequency or rate of speed,--thousands and thousands of times a minute ; and this current as it reaches the telephone at the near or the distant station causes the diaphragm of that instrument to emit a musical note characteristic of that current whenever it is generated at just that "frequency" or rate of vibration in the circuit. The rest is relatively easy. The revolving parts of the little alternators are mounted upon shafts, which are geared together. Each revolving part, or "rotor," having its own number of poles, or teeth, in the magnetic field of force, and each having its own angular velocity, the arrangement gives us the ability to produce, in the initial condition of musical electrical waves, the notes through a compass of five octaves.

When an organ is played, a boy, or now quite often an electric motor, pumps the

bellows. When the telharmonium is played, a motor similarly sets it going., so

that all the little interlocked rotors are revolved at once and offer their

plastic currents to the facile touch of the performer to whose keyboard the

wires from the alternators lead. This keyboard is shown in one of the

engravings, and has two banks of keys to accommodate all the notes thus made

available. If one key is depressed, the circuit is closed on a ground tone and

one or more allied circuits that will give the harmonics corresponding to that

tone. But the currents, before they go to the exterior circuit containing the

subscriber's telephone are not left in their primitive simple form. On the

contrary, they are passed, as they might be in ordinary lighting and power

service, through transformers, where they are blended ; and in these "tone

mixers" the simple sinusoidal wave of the alternator current becomes too complex

to know itself. In this manner highly composite vibrations are built up which

fall upon the ear as musical chords of great beauty and purity of tone. This

process of interweaving of currents can be pushed very far, and the complex

vibrations from different keyboards can be combined into others even more subtly

superposed and wedded so as to produce in the telephone receiver the effect of

several voices or instruments Within the range of such an equipment appear

possible some sounds never before heard on land or sea.

The performer at this keyboard has a receiver close at his side, so that he can

tell exactly how he is playing to his unseen audience ; and it is extraordinary

to note how easily and perfectly the electric currents are manipulated so that

with their own instantaneity they respond to every wave of personal emotion and

every nuance of touch. It is, indeed, this immediateness of control and the

singular purity of tone that appeal to the watchful listener. A musician will

readily understand how the timbre is also secured from such resources, for with

current combinations yielding the needed harmonics, string, brass, and wood

effects, etc.; can be obtained simply by mixing the harmonics,--that is, the

current,--in the required proportions.

(Thomas C Martin: The Telharmonium: Electricity’s Alliance with Music, Review of Reviews, April, 1906, p.p.420-423)

-------------

Dr. Thaddeus Cahill, the inventor, declares that it is as easy to create music at the other end of fifty miles of wire as to send a telegraph message. At a keyboard of his device a performer--or there may be two--lightly presses down the keys, and at receivers, perhaps many miles distant, music pours forth. In pressing the keys the performer throws upon a wire a vibration--or a set of vibrations--which turns into aerial vibrations or audible music, when it reaches the diaphragm of a telephone receiver. The vibrations stand for notes and tones, and they scurry along to do their work the instant they are released. The performer is conscious only of the music he produces. He does not necessarily hear it.

He need know nothing of the mechanical process he sets in action by the pressure

of his fingers on the keys. Yet under his fingers the electrical vibrations act

tractably and instantaneously. At will he turns an exhaustless supply of

different kinds of vibrations to produce at a distance just the sounds he

desires.

Only those wise in electrical knowledge will ever understand just what has taken

place in the Cahill laboratory, but in bare outline it is this: An

alternating-current generator has been built up for each note of the musical

scale. Each of these generators produces as many electrical vibrations per

second as there are aerial vibrations per second in the note of the musical

scale for which it stands. From the generators a mass of wires leads to the

keyboards. The keys operate switches which conduct the desired vibrations from

the generators, much as in a pipe organ the player, by pressing certain keys,

turns the air from the bellows into different pipes to produce the tones he

desires. These vibrations are passed through several transformers or tone mixers

to become still more complex, and then the interwoven vibrations go forth on a

wire.

Although the process seems involved, the action is instantaneous. The performer

presses the key which sets in motion a set of electrical vibrations,

corresponding to a note, and in a thousandth of a second the note sounds with

perfect distinctness and purity from the receiver, whether it be at the

performer's elbow or many miles away.

In the music room where the performer sits, there would be absolute silence, if

it were not for the receiving horn placed near him, so that he can judge of the

character of his playing. The vibrations do not turn into sound until they reach

the telephone receiver. Yet the wires all the time are full of silent music,

which could be distinguished if the ear were constructed to catch electrical

vibrations as it is to catch aerial vibrations.

In a small dark room close by the music room is a long box in which are 400

telephone receivers attached to the instrument but with their noses buried in

sawdust so that their voices are silent. If a handful of them are dragged out of

their sawdust bed, however, they sing out loudly on the air. The wires between

the instrument and the receivers may be tapped anywhere to give forth musical

sounds, and when Dr. Cahill completes his system, he may literally fill the

world with a network of music.

The possibilities of this new musical instrument are almost limitless, for not

only can it produce the tones of almost all the known orchestral instruments,

but it creates musical sounds never heard before. The tones of the different

orchestral instruments are secured by mixing with the ground tone one or more

harmonics in the required proportions. For instance, at a touch of the third and

fourth of the harmonic stops, which are located above the keyboard, something in

the manner in which organ stops are arranged, the performer may change a

flute-like note to the sound of a clarinet, or, by using all the harmonics up to

the eighth, the tone may be transformed into a string sound. Another combination

of harmonics gives the strident sound of brass. As a final triumph a musician

can so combine the harmonics as to produce musical timbres unknown before. He

may develop an almost limitless number of new sounds according as his patience

and his soul direct. Electrically he produces the different musical timbres by

mixing vibrations of different frequencies. The effect of a full orchestra is

brought about satisfactorily when two players are at the key-board.

One of the most remarkable features of the device is the delicacy of control. It

lends itself instantly to expression, and responds more sympathetically to the

soul of the musician than any other instrument, with the exception, perhaps, of

the violin. It is as sensitive to moods and emotions as a living thing. The

performer by a mere touch controls the various shades of the notes, and varies

them at will. The three musicians who are perfecting themselves in the mastery

of the instrument at the Cahill laboratory, find to their delight that all the

varying meanings and emotions of classical music may be brought out

artistically.

To play electrical music a performer must have some knowledge of the piano and

must be a thorough musician. So delicate is the instrument that listeners at a

receiving station many miles distant may detect the difference in touch of the

players. A Bauer or a Paderewski at the instrument could delight an audience ten

miles distant as thoroughly as if the listeners were in the concert hall with

the musician. The keyboard has two banks of keys, a row of stops to regulate the

harmonics, and a few other devices which help to determine the expression. But

there is not a pipe, a string, or a reed in the entire apparatus. Everything is

electrical.

At the receiving stations the device is simply a telephone receiver attached to

a large horn, like that of a phonograph. The telephone receiver may not be held

to the ear, for the current is so strong that its effects would be injurious.

For, whereas a current of only six ten-millionths of a millionth of an ampere is

sufficient to produce a sound in an ordinary telephone receiver, in the Cahill

system a current of an ampere is sometimes used for an instant for loud tones.

In consequence of the strength of the current, the musical tones are not marred

by any of the noises along the line such as oftentimes seriously disturb the

feebler current of the ordinary telephone.

The invention is not in the experimental stage. The first commercial

installation has been completed. The second is being constructed and will

probably be placed in New York City as a central station for distributing music.

The machine already finished is a massive device of metal and wires. It weighs

more than 200 tons and cost $200,000. There are 145 of the alternating

generators grouped in eight sections and the switchboards, including nearly

2,000 switches, are in ten sections. Music was sent successfully from Dr.

Cahill's original laboratory to New Haven , a distance of 70 miles over a leased

wire. In a Holyoke hotel, a mile distant from the central installation, where

two receiving horns, have been stationed, a large ballroom is filled with the

music. There is none of the rasp and harshness of the phonograph about it; its

tones are pure, clear, round, and rich. By the very nature of the mechanism the

instrument is permanently tuned.

The most important feature commercially of the electrical music is that it may

be produced simultaneously in thousands of places many miles apart with as much

power as if an orchestra were in every one of the places. Several of the

generators for single notes send out from 15 to 19 horse-power. Notes with

several horse-power behind them naturally have no difficulty in supplying many

receiving stations at once. All that is necessary to release the music at a

receiving station is the moving of a tiny switch.

Dr. Cahill plans to place the system at first in theatres, concert halls,

restaurants, hotels, and department stores, but later he expects it will come

into private use. In small towns where fine music is rarely heard a connection

could be made with private homes from the central station in a large city and

the masterpieces of music could be heard at will. The electrical music will go

over its own wires and not over leased wires. Central stations will probably be

not more than fifty miles apart, in order to get the best results. There will

probably be operators or performers at the central station for twenty-four

hours, and music will be on tap all hours of the day or night. An individual may

go to sleep to music or rise to it according to his temperament, and a hostess

may furnish an orchestra for her dinner party at the turn of a button. As the

system develops, Dr. Cahill is hopeful that in due time there may be four sets

of mains fed from the central station, each with a different kind of music, and

by connecting the four sets of mains to a public place or a private home,

rag-time ditties, classical compositions, operatic, or sacred music may be

turned on according to one's mood.

(Marion Melius, Music By Electricity, The World's Work, June, 1906, pages 7660-7663)

The instrument was installed in a building at 39thSt and Broadway, with the workings in the basement and the console in a concert room at street level, where speakers of a primitive nature were provided so that audiences and potential customers could hear it, as well as those to whom its sounds would be transmitted via the New York telephone system. The initial concert was presented on 26 September, 1906, being the first public performance of an electronic organ in history.

Subscribers to the piped music began to be signed up. The first, on 9 November, 1906, was New York ’s Café Martin on 26th St. It was not long before complaints started to arrive from those whose telephone conversations were disturbed by cross-feed from the separate music lines laid alongside the ordinary telephone lines. There are stories of at least one financial magnate who is said to have wreaked physical violence on the instrument that had interrupted his wheeling and dealing on the telephone. Nonetheless, the number of subscribers expanded that winter, and included not only such establishments as the Casino Theatre, the Museum of Natural History and the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, but also several wealthy private individuals who had the music piped to their homes. Many public performances were presented in the building on Broadway where the instrument was installed, which by now had been named Telharmonic Hall.

Among the private subscribers was Mark Twain, who said about the Telharmonium in late 1906:

“The trouble with these beautiful, novel things is that they interfere so with one's arrangements. Every time I see or hear a new wonder like this I have to postpone my death right off. I couldn't possibly leave the world until I have heard this again and again."

Mark Twain said this as he lounged on the keyboard dais in the telharmonium music room in upper Broadway, swinging his legs, yesterday afternoon. The instrument has just played the "Lohengrin Wedding March" for him.

"You see, I read about this in THE NEW YORK TIMES last Sunday, and I wanted to hear it. If a great Princess marries, what is to hinder all the lamps along the streets on her wedding night playing that march together? Or, if a great man should die -- I, for example -- they could all be tuned up for a dirge."

"Of course, I know that it is intended to deliver music all over the town through the telephone, but that hardly appeals as much as it might to a man who for years, because of his addiction to strong language, has tried to conceal his telephone number, just like a chauffeur running away after an accident” – (http://www.twainquotes.com/19061223.html)

The last thing Mark Twain did in 1906 was to get drunk and deliver a lecture on temperance, and the first thing he did in 1907 was to glory in the fact that he would be able to rejoice over other dead people when he died in having been the first man to have telharmonium music turned on in his house - "like gas." - (http://www.twainquotes.com/19070101.html)

Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) had provided financial backing to Cahill, as he had earlier done for Robert Hope-Jones, prior to the latter joining forces with Wurlitzer. As he finished his New Year speech (above), it was midnight. “Auld Lang Syne” and “ America ” were then heard piped from the Telharmonium. (Albert B Payne, Mark Twain: A Biography, New York, 1912, p. 1365)

Also during the period around Christmas, 1906, Lee de Forest was developing his “audion” valve radio receiver, and transmitted some experimental wireless broadcasts of the Telharmonium. These were almost certainly the first wireless broadcasts of any type of organ. Here, again, cross feeding caused problems, and the US Navy was far from impressed when its ships picked up the strains of organ music rather than information and orders concerning their manoeuvres. (Gavin Weightman: Signor Marconi’s Magic Box, London , 2003, p.208)

Performances on the Telharmonium were usually from the popular classical repertoire, including Beethoven, Chopin, Greig, Rossini, etc. The cross-talk problems and a financial “Panic” in 1907 militated against the venture’s commercial success. The last public concert was given in February, 1908, and by May, 1908, the company was no longer in business; the doors to Telharmonic Hall closed, and the second version of the Telharmonium was dismantled and returned to Holyoke .

But all was not yet over. Cahill constructed a third Telharmonium, larger and more powerful than its predecessors, which was ready for its public unveiling at Holyoke in 1910, and installation in August 1911 in a building at 553 W56th St, New York City. It was demonstrated at Carnegie Hall in February, 1912, but the third Telharmonium did not generate the interest of its forerunner, and now that wireless was providing more competition, it gained little success. By 1914, Cahill’s company was bankrupt, and the instrument was dismantled. A final patent issued in 1917 consolidated the improvements the final version had incorporated.

Sadly, although the first prototype Telharmonium survived until the 1950s, no one was interested in it, and Cahill’s brother Arthur sold it for scrap after circulating a final appeal for someone to save it in 1951.

Arthur had been keeping the historic 14,000 lb Telharmonium prototype in storage at his own expense for almost 50 years, and finally sought "a permanent and a public home for this priceless monument to man's genius." There were no takers, and not even a small part of this incredible music machine is now available to wonder at.

Mark Sinker Singing The Body Electric, The Wire, September 1995, issue 139

Its technology provided the concept for the Hammond organ that was developed in 1934; by then, efficient amplifiers and loudspeakers meant that the huge rheotomes could be replaced by small wheels and what had previously required 200 tons of equipment could be contained in a console smaller than a grand piano.