Theatre Organs in Australia

The start of it all

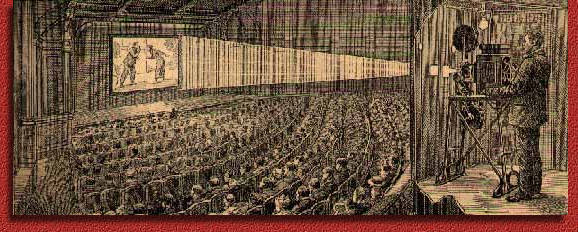

It was in August, 1896, that Australian vaudeville audiences first witnessed the new technological

wonder which was to revolutionise "show business" and dominate the nation's entertainment for

the next sixty years. From being part and parcel of vaudeville shows, picture shows in their own right soon became established, the first being Falk & Co.'s,

located at 237, Pitt St., Sydney [Ian Griggs, The Story of the Arcadia

Cinema, Chatswood, Sydney, 1972]. This was quickly followed by

many others, in temporary and permanent

accommodation, across the nation.

many others, in temporary and permanent

accommodation, across the nation.

"All over the country tin sheds appeared. Old barns were confiscated, and swept and garnished. A few forms, a sagging sheet and a few day bills on a convenient fence - and, hey presto! - a Picture Show."

[Everyone's, 4 January, 1928]

From these humble origins arose progressively

elaborate picture shows - it does not seem

appropriate to refer to them yet as theatres - in

which the silent dramas on the more or less silver

screen would be accompanied by the clatter of the primitive

projection equipment, with, in some cases a jangling piano, the

latter more to mask some of the noise of the former than to enhance the dramatic effect. The

atmosphere of these early shows has been captivatingly recreated in Joan Long's 1977 film "The

Picture Show Man".

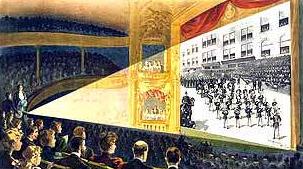

In time, the better-class establishments introduced small orchestras. From around the first decade of the twentieth century, organs also began to be used. Where and when this first happened is not certain.

A number of buildings used for picture shows in the early days both contained organs. The Tivoli Theatre, Melbourne, contained a single-manual Casson organ which was installed in around 1899. The Queen's Hall, Perth, housed a second-hand two-manual Bishop organ, installed there in 1908. The Queen's Hall was owned by the Methodist Church and was used for Sunday church services. On weekdays, though, it was the venue for Vic's Pictures. The Lyceum Hall in Sydney housed a substantial Fincham organ. It is quite likely that any of these instruments could have been used to provide film accompaniments, either solo or with an orchestra, the first such use of an organ in Australia.

"The Story of the Kelly Gang" (1906)

The first recorded use of an organ at a film performance was at the opening of

the Crystal Palace Theatre, Sydney, on 24 June, 1912. The Crystal Palace

represented the last word at that time in elegance and refinement. Its many

attractions included "a Vox Humana pipe

organ to accompany films and an

orchestra". [Ross Thorne, Picture Palace

Architecture in Australia, Melbourne, 1976] This

pioneer instrument, a two-manual Estey

organ, perished in a fire in 1921.

A number of the more prosperous theatres which opened in the 1910s and early 1920s contained small pipe organs. These were used in many cases in conjunction with orchestras, both to augment them and to provide film accompaniments for the less important daily sessions when the orchestra was resting. Most of these instruments were fitted with mechanisms so that they could play automatically from paper rolls. This type of instrument, which comprised a piano, from two to eight ranks of pipes, perhaps some harmonium-type reed stops, and a wide variety of drums and silent picture sound effects, was known as a "photoplayer".

However, apart from the city theatres, which often employed quite sizeable orchestras, most picture shows were accompanied by music from player pianos, or "pianolas", as they were generally, and in most cases incorrectly, described. ( "Pianola" was the trade mark of the Aeolian Company in America, and thus technically only denotes instruments produced by that company).

These ranged in quality from the £600 Steck Duo-Art reproducing piano installed in the Strand Theatre, Rockhampton, Qld., [Everyone's, 22 March, 1922] to tinny, sub-standard instruments.

Operation of these instruments often formed one of the duties of the theatres' usherettes, who were not generally noted for their musical appreciation, although there were exceptions:

"There is nothing worse than a badly-played

pianola; and at the same time, nothing gives as

much satisfaction to an audience as a well-played

piano. Many a good picture is spoiled by bad

music; and this is our experience almost every

week, as the representatives of this paper witness

the various releases during the "off" hours of the

day... For the sake of a little extra in salary, a

competent instrumentalist would manipulate the

pianola in a thorough manner - at the same time

switching to appropriate music when occasion

called for it, by discarding the roll in favour of

personal manipulation."

[Everyone's, 14 September, 1921]

"What is worse than the continual stoppages of the pianola, or an incomplete melody being taken up by another roll on the same instrument? Nothing that we know of. And yet this should not be. An operator with a soul for music could amend a majority of these shortcomings, but it is usually noted that these musicians(?) have no conception of what is needed."

[Everyone's, 7 June, 1922]

"Most of the girls who manipulate a pianola in one or other of the city

theatres use their ears for any other purpose but melody. Thus it

happens that when a worthwhile exponent of this much-maligned

instrument comes along, a little pat on the back is not out of order. This

honour is therefore bestowed on the little lady who handles the

mechanical instrumental programme at the Piccadilly Theatre, Sydney.

She certainly makes the music worth listening to." [Everyone's, 9 August,

1922]

Even where pianists and orchestras played, all was not beyond criticism:

"The writer, in going the rounds of the picture shows, has often tumbled on strange and weirdly imaginative musical directors. On one occasion, a gazette included "The Burial of the Unknown Warrior", a living memory to our dead, and throughout, the musicians kept on playing the lively ragtime music that they were playing for the previous episodes in the newsreel. The effect was astounding, and lack of attention on the part of the director doubtless had the effect of offending many of the patrons.

"On another occasion, I happened to call at a picture show in the country, and found a "Feature" pianist employed. "From Manger to Cross" was being screened, and when it came to the scene showing Jesus walking on the water, our friend of the keyboard struck up "A Life on the Ocean Wave". Here was indeed an example of misplaced humour and bad taste, probably offensive to ninety per cent of the patrons who noticed it.

"In many of the larger picture theatres, very good orchestras are engaged, but somehow or other, the selection of music is often far short of suitable. I am quite aware of the difficulties of obtaining "suitable" music, but the trouble seems to be a lack of knowledge on the part of the persons responsible for the selection of the melodies.

"It seems to be the general rule that if a "big" picture comes along, the music must also be "big". Away flies the director to his library and selects the biggest and most ponderous "Overtures" or "Selections" he can find. Now what in all that is wonderful do grand opera overtures or classical selections to do with the picture?

"I admit, of course, that in some cases portions of them may be used, but not generally. Another mistake made very often by our enterprising musicians is the playing of popular selections of musical comedy during a drama. The minds of the patrons familiar with the airs and words of these compositions immediately revert to the stage where they originally heard them, and focuses attention away instead of on the picture being screened."

[Fred Mumford, "Music and the Photoplay", Everyone's, 11 May, 1921]

Even some of the early organ installations were not unqualified successes. The instrument at the Grand Theatre, Adelaide, which had received glowing testimonials when installed, was replaced by an orchestra in August, 1922, when Horace Weber left, and no adequate replacement organist could be found. [Everyone's, 16 August, 1922]

Organist Manny Aarons used to recount that at one theatre where the organ was played by rolls during the organist's rest periods, a disgruntled patron once threw a banana into the player unit.

This, however, was nothing in comparison with the drama which took place in a Sydney theatre in December, 1922:

PICTURE THEATRE SENSATION

"Last week a sensation occurred at the Majestic Theatre, Liverpool Street, Sydney, when Francis George Fraser, 34, aimed a revolver at Ethel Frances Eggins, who was manipulating the pianola. The girl, who was uninjured, screamed, and Fraser was arrested, charged with carrying firearms without a licence.

"On examination, it was found that a loaded six-chambered revolver had missed fire in five cartridges, otherwise a more serious charge would most likely have been preferred. Accused and Miss Eggins were on good terms, prior to the attack.

"Fraser, who will be charged with attempted murder, was refused bail." [Everyone's, 20 December, 1922]

This report is of interest in that it gives us the name of one of the "pianola manipulators", the rest, it seems, having faded into anonymous memory.