1933 - 1960

1933 - 1960

1933 - 1960

1933 - 1960

By 1933, things were beginning to improve a little, and Sydney's Western

Suburbs Circuit embarked on a programme of expansion, introducing an

imaginative organ policy. Western Suburbs took over the Roxy Theatre,

Parramatta, and had also installed in 1932 a three-manual, ten-rank Christie

organ in the Palatial Theatre, Burwood. This interesting instrument had

originally been installed in the Clou Konzert Haus in Berlin, and had even

been pictured there in some of Christie's early Australian advertisements

[Everyone's, 7 August, 1929, p. 43]. It had been removed after only a short stay in

Berlin (probably because of payment defaults) and had been sent to the

Melbourne factory for installation in the Civic Theatre, Auckland, New

Zealand. However, a Wurlitzer organ was installed in Auckland, so the 3-10

Christie remained in the factory awaiting a purchaser.

In 1934, Western Suburbs opened the Civic Theatre, Auburn, NSW, in which was installed a two-manual, thirteen-rank Wurlitzer organ. This instrument had previously been installed for demonstration purposes in the home of Wurlitzer's Australian agent, where it had comprised ten ranks. A further three, rather overscaled, ranks were added for its new rôle in the cinema.

The following year saw the installation of an eight-rank Christie organ at the Melba Theatre, Strathfield, Western Suburbs' HQ theatre. This organ was rebuilt from the five-rank instrument at the Ritz Theatre, West Concord, and presumably the necessary additions were manufactured at Hill, Norman & Beard's Melbourne factory.

By now, Union Theatres were in dire financial trouble. The theatres were losing some £4000-5000 per week [Ken Hall, Australian Film, The Inside Story, Dee Why West, 1980, p. 96], and the film distributors not already committed to Hoyt's were flocking in that direction, leaving Union with only Universal, British Empire Films and its own subsidiary, Cinesound [ibid, p. 108]. It was Cinesound which pulled Union out of its financial difficulties and enabled it to survive. In 1980, Greater Union had 175 theatres [ibid., p.110].

MGM had commenced building a small chain of Metro theatres, its first opening in Melbourne in April, 1934, followed by Brisbane (1937), Perth (1938) and Adelaide (1939). The Metro Theatre, Perth, was a rebuild of the Regent, which retained its Wurlitzer organ, the only organ in an Australian Metro theatre. It is to be regretted that this chain developed so late, as otherwise, like the Metros in South Africa, those in Australia might have been provided with fine organs.

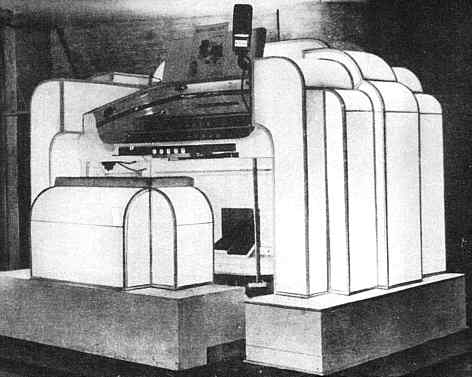

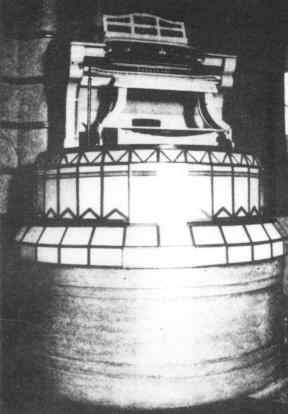

It was left to Western Suburbs to maintain the tradition of installing organs in their new "supers". Since 1932, the consoles of many theatre organs installed in Britain had been adorned with increasingly elaborate glass surrounds which enclosed multi-coloured lights capable of being set to some eight different colours, or set automatically to merge from one colour to another in cyclical sequence. These were immensely popular with British cinema audiences in the 1930s (and today remain one of the instrument's best remembered features there), and no doubt Western Suburbs had heard of this success, possibly through Christie, who naturally enough would have been kept fully informed about this development by its British parent company.

Thus, when Western Suburbs ordered a five-rank Christie organ for their new Astra Theatre, Parramatta, an illuminated console surround was included in the deal. The entire instrument, including the surround, was built in Australia, and the console surround quite closely resembled several British installations. The instrument was opened on 18 February, 1937.

Another Western Suburbs cinema opened on 4 September, 1937. This was the Savoy Theatre, Hurstville, and in it was installed the ten-rank Wurlitzer organ originally installed in the King's Cross Theatre, Darlinghurst, NSW, in 1928.

The following year, another new organ with an illuminated console surround was installed in the Astra Theatre, Drummoyne, NSW, which opened on 8 April, 1938. This instrument has gained a niche in theatre organ lore and legend as one of the strangest contraptions to grace a theatre. It was a mish-mash of ill-assorted bits and pieces collected by organist Penn Hughes, the theatre management and various other people. These parts were assembled into a kind of organ by Mr Bert Ferrie of the G H Martin Organ Company. It nominally comprised eight ranks of pipes, but little more than half of it ever seems to have functioned, at least at any one time. One of its three manuals is reputed never to have been connected. It soon gained amongst organists the sobriquet "The Thing at Drummoyne" (plus some other rather more graphic descriptions) and, not surprisingly, was heartily disliked by all who had to attempt to play it. Its ignominious career was mercifully brief.

"The Thing at Drummoyne"

The console illuminations at Parramatta and Drummoyne (and for several Hammond organs installed in cinemas) were constructed by F W Gissing Pty. Ltd., of Newtown, Sydney, but whether they used British patents is not known. "The play of colour through the opal glass, with ever changing hues in endless variety, make this console a thing of surpassing charm." [Opening brochure, Vogue Theatre, Double Bay, NSW, 13 May, 1938]

The next organ installed by Western Suburbs was a Christie, but this did not have an illuminated surround, although its lift was illuminated. It was by no means new, and is an instrument we have encountered successively at the Regent Theatre, North Perth, the De Luxe Theatre, Melbourne and the Plaza Theatre, Sydney. In none of those locations does it appear to have been much loved, and after eight years at the Plaza, it was removed and replaced by the Wurlitzer organ from the Wintergarden Theatre, Brisbane. It found a new home at the Savoy Theatre, Enfield, NSW, which opened on 27 July, 1938. Here, at least, it was successful, and enjoyed a lengthy sojourn of some twenty years. It was Western Suburbs' last new pipe organ installation.

Savoy, Enfield - Christie 2/8

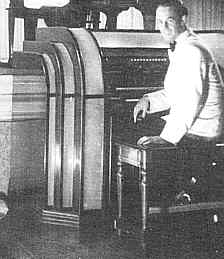

By this time, a few cinemas in Australia contained Hammond organs, often with illumin ated

surrounds. The Encyclopaedia is primarily concerned with pipe

organs, and thus these and other pipeless electronic organs

installed in cinemas do not really fall within its scope. However, they

deserve a mention in passing, as it is unlikely that the average

cinema patron could tell that there was a difference between them

and theatre pipe organs, or even cared. Some of the best-known

Hammond organ installations were at the Century Theatre, Sydney,

the Vogue Theatre, Double Bay, and the Savoy Theatre, New

Lambton, Newcastle. The Double Bay organ was claimed to possess

"the most beautiful console in Sydney" [Opening brochure, Vogue Theatre,

Double Bay, NSW, 13 May, 1938], a claim that many would question.

ated

surrounds. The Encyclopaedia is primarily concerned with pipe

organs, and thus these and other pipeless electronic organs

installed in cinemas do not really fall within its scope. However, they

deserve a mention in passing, as it is unlikely that the average

cinema patron could tell that there was a difference between them

and theatre pipe organs, or even cared. Some of the best-known

Hammond organ installations were at the Century Theatre, Sydney,

the Vogue Theatre, Double Bay, and the Savoy Theatre, New

Lambton, Newcastle. The Double Bay organ was claimed to possess

"the most beautiful console in Sydney" [Opening brochure, Vogue Theatre,

Double Bay, NSW, 13 May, 1938], a claim that many would question.

Wilbur Kentwell at the Hammond Organ

Savoy Theatre, New Lambton (Newcastle)

The close of the era of theatre pipe organ installations in Australia was marked by the outbreak of World War II. There was only one new installation during the war, at the privately-owned Regent Theatre, Wentworthville, where a small Wurlitzer, formerly in Romano's Restaurant, Sydney, and later in a residence, was opened on 24 August, 1940.

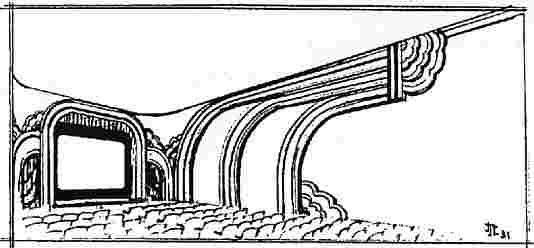

Most of the cinemas built during the 1930s were very different from the lavish and elaborate picture palaces of the previous decade.

New King's, Mosman (above)

Savoy, Hurstville (left)

"The luxury cinemas were deliberately designed to create an environment of which the movie-goer could feel no part; a vision of an exotic, aristocratic

world where the fan had to play the permanent

onlooker. In the modernised suburban cinemas,

movie-goers were relaxed participants in buildings

inspired by domestic surroundings. Instead of

looking like a ballroom at Buckingham Palace,[This

was no hyberbole. The foyer of the Gaumont State Theatre in

the London suburb of Kilburn was indeed a replica of the

ballroom at Buckingham Palace. The later placement of a

perspex, laminex and plastic Candy Bar in the centre of the

foyer did little to enhance the gilt, crystal and marble surrounding

it…] the theatre foyer now resembled the ideal family

sitting room; the stress was on symmetry, comfort

and order, with details like the lighting now

designed not to dazzle but to 'calm and soothe'.

could feel no part; a vision of an exotic, aristocratic

world where the fan had to play the permanent

onlooker. In the modernised suburban cinemas,

movie-goers were relaxed participants in buildings

inspired by domestic surroundings. Instead of

looking like a ballroom at Buckingham Palace,[This

was no hyberbole. The foyer of the Gaumont State Theatre in

the London suburb of Kilburn was indeed a replica of the

ballroom at Buckingham Palace. The later placement of a

perspex, laminex and plastic Candy Bar in the centre of the

foyer did little to enhance the gilt, crystal and marble surrounding

it…] the theatre foyer now resembled the ideal family

sitting room; the stress was on symmetry, comfort

and order, with details like the lighting now

designed not to dazzle but to 'calm and soothe'.

"In a decade of dole queues, desperation and

hunger, the local cinema radiated

reassurance. Where the imagery of the picture

palace was drawn from the past, the

architecture of the 1930s and 1940s cinemas

was cleverly future-oriented: the very buildings,

confident

and modern,

seemed to

confirm that

there were

better things

to come.

Symbols of freedom and renewal were almost routinely

incorporated into the decorative effects - art déco sunbeams

and rising suns were especially popular and so, too, were

representations of rushing winds, clouds, hair streaming in

the breeze and, at

the Cremorne Orpheum and Melbourne's

Century, 'Nordic youths

gambolling under a blond Aryan

sun'. There could have been few

more fitting motifs with which to

embolden picture shows in the

Depression and post-Depression

years than these images of Nature:

regenerative, eternal and free to

all." [Diane Collins, Hollywood Down Under, North Ryde, NSW, 1987

pp. 130-2]

the Cremorne Orpheum and Melbourne's

Century, 'Nordic youths

gambolling under a blond Aryan

sun'. There could have been few

more fitting motifs with which to

embolden picture shows in the

Depression and post-Depression

years than these images of Nature:

regenerative, eternal and free to

all." [Diane Collins, Hollywood Down Under, North Ryde, NSW, 1987

pp. 130-2]

New King's Theatre, Mosman (1937)

In June, 1944, A J Baszant's Western Suburbs circuit of 23 cinemas, including eight with pipe organs, was sold to Hoyt's [Barry Sharp, Showcases of the Past, NSW TOSA News, Sydney, March, 1976, p. 6], and thus almost every Australian theatre organ was now under the control of either Hoyt's or Greater Union, as Union Theatres were by now known.

The early years of Word War II brought an end to the resurgence of the fortunes of the Australian cinema industry. In 1939, there were 1371 cinemas in operation [Robertson, Patrick, The Guinness Book of Film Facts and Feats, Enfield, Middlesex, UK., 1980 p.205], but by June, 1940, "the theatres in Australia reached their lowest ebb since the depths of the Depression. More than a few suburban theatres went dark, and many city theatres might just as well have closed for all the good they were doing" [Ken Hall, Australian Film, The Inside Story, Dee Why West, 1980, p. 119].

However, once the Pacific War developed, "programmes did not really have to be sold by high-powered and first-quality advertising. It was a matter of opening the theatre doors and allowing the tide of entertainment-hungry humanity to flow in. Theatres were allowed to open on Sundays, an unheard-of practice previously. That privilege was withdrawn immediately after the war" [Ken Hall, Australian Film, The Inside Story, Dee Why West, 1980, p.155]. Such were (and still are) the fickle fortunes of the cinema industry; as they say, "That's show business!"

On the night of 29/30 April, 1945, there was a disastrous fire at the Regent Theatre, Melbourne. The entire auditorium was gutted and everything in it destroyed, including the magnificent four-manual, twenty-one rank Wurlitzer organ. Once post-war building regulations permitted, it was reconstructed, much on the same lines as before, but with a more angular proscenium. It reopened on 19 December, 1947.

Theatre organs still retained popularity, and the Regent's organ was being featured daily until the fire. Thus, a four-manual Wurlitzer organ was installed in the rebuilt theatre. Wurlitzer had ceased pipe organ production some years previously, so the "new" organ was a rebuild of the fifteen-rank organ from the Ambassador's Theatre, Perth, of which the console was reconstructed to house four manuals, and to which four extra ranks, derived from pipework from the Paramount Theatre, Melbourne, Wurlitzer, also removed at this time, were added. The result was a four-manual, nineteen-rank instrument with a very distinctive lush and sweet-toned sound. It was Hoyt's last "new" installation.

The end of the war was also marked by the acquisition, reputedly for £750,000, by the British Rank Organisation, of a half-interest in the Greater Union Theatre Group and its film-making and other subsidiaries [Ken Hall, Australian Film, The Inside Story, Dee Why West, 1980, p. 144].

For the next few years there were no major developments in the Australian theatre organ scene, but in the mid-1950s, the arrival of television and its consequent impact on cinema audiences led to cost-cutting exercises by Hoyt's and Greater Union, now controlled by accountants, rather than the visionary showmen who had created the circuits.

Organists began to be dismissed, and organs were removed from theatres. By 1960, only a handful of theatre organs remained in daily use, and many instruments had gone to new homes, some to churches, some to private homes, others to store.

New York Movie - Edward Hooper

Museum of Modern Art, New York City