The following three-part article was published in the academic British musical journal "The Musical Times" in its issues dated September (pp. 662-3) and November, 1938 (pp. 817-9) and January, 1939 (pp. 21-22). Its author had for many years been a cinema organist, performing as "Wilson Oliphant", recording on 78 rpm discs both solo and with Hal Swayne's band (from the London's Café Royal), as well as a renowned church organist and composer - his "Paean" has for many years been a recital favourite, especially on concert organs. The article is of particular interest in that it provides witty and insightful commentary from the "inside" on the trials and tribulations of the job of a cinema organst a decade after the passing of silent films. Is it cynical, a little jaundiced maybe (nostalgic for the halcyon days past?), or just depicting things as they were? It does reveal that it wasn't all just the glamour of white suits, spotlights and illuminated consoles; as to the individuals and organisations to whom the author alludes, we can only speculate as to their identities.

Wilson Oliphant's career was documented in "Theatre Organ World" in 1946 and documents his credentials to provide advice to those considering becoming cinema organists just before the war:

OLIPHANT, WILSON, Mus.Bac., F.R.C.O.

As most people know, Wilson Oliphant is the console name of Oliphant Chuckerbutty, a composer, church and concert organist. Studied the piano at the age of six, and was composing at the age of 14. Deputised as assistant organist Southwark Cathedral to Dr.E. T. Cook for six years, terminating at the outbreak of the first world war. Taught piano technique by Epstein. Is a Fellow of the Royal College of Organists and graduated as Bachelor of Music in London University. Had first song, "An Old Song," published by Boosey in 1914. Immediately after the war started a dance band and ran it for several months, after which he took up cinema organ work, opening at the Marlborough Theatre, Holloway. Quentin Maclean once described O. as "the only organist I know who combines whole-time cinema work with whole-time church work and makes a job of both." Joined the musical staff of Angel, Islington, 1920, and played there until 1927. Was kept busy teaching all the time, also at the church and composing. Left the Angel in 1927 and held numerous other posts, including: Café Royal, Regent Street; Shoreditch Olympia; Ritz Edgware; Carlton, Essex Road; New Gallery and now Forum, Kentish Town. Made several hits with such pieces as "Souvenir d'amour," "Vision," "Fiesta Argentina" and many others. Newest composition, "Two May Day Dances" B.and H. Occasionally broadcasts. Many recitals include Albert Hall; Colston Hall, Bristol; Crystal Palace, etc.,etc. 0rganist and choirmaster Holy Church, Paddington, where he has been for a long time. Married. Wife, L.R.A.M. (piano).

To be or not to be -

a Cinema Organist

By S. W. CHUCKERBUTTY

These notes are primarily intended for the information of church organists who are interested in cinema work and would like to know more about the outlook and prospects of a cinema career.

Much depends on the temperament of the individual.

Is he adaptable? Does he feel drawn towards light music? Can he revolutionize all his preconceived notions about organ technique?

Or is he a person who cannot easily change his point of view, likes only the best of serious music and detests all kinds of 'stunts' and showmanship? If he is to be found in the latter category cinema success is hardly likely to be reached by him. His life will probably be one of not too refined torture.

It is highly necessary in this work to 'go the whole hog.' Musically, you must be born again if you have received a first-rate training. If you are self-taught, delight in dance music and play the piano in a dance band, you will probably find little trouble in adapting yourself. But the man I have in mind in writing these articles is the church organist, good at his job but unable to live on his salary and teaching. Such a man may be excused for turning to cinema work for improved circumstances, and some no doubt will, as in the past, be successful. Unless, however, he is in monetary straits I would advise no serious young man with a chance of a 'straight' musical career ahead of him to think of cinema work.

One thing I must in fairness say: it will not spoil your playing, but will give it more ease and flexibility.

Let us suppose that you have decided to follow a cinema career: what next?

Ten years ago the answer would have been simple: any efficient organist and good sightreader could easily obtain regular work playing the organ with one of the numerous excellent orchestras then functioning in most cinemas.

Here it was possible to acquire a repertory and a feeling for the symphonic style of playing which was then in demand. After a short apprenticeship the aspirant could go to solo work, accompanying silent films; this was work worth doing as well as one could possibly do it.

But that was ten years ago: now all is changed. There are few bands, and the ones that exist (being dance combinations) rarely need an organ.

No longer is it sufficient to be a good player. Indeed, what is meant by 'good' playing is now definitely classed as 'bad' in cinema circles. The person most in request seems to be the jazz pianist who has practised a few times on a unit organ and has simply transferred his jazz playing en bloc to the organ, with an occasional pedal note, 'obbligato.' You are expected to emerge fully fledged, a 'star' player of interludes in a style with which you are probably unfamiliar and which in any event you detest.

The crux of the matter is that there is now no room for beginners. Opportunities for deputizing are becoming rarer every day. 'Second' organists are almost unknown ; orchestral organists have ceased to be; bad organists are numerous, and preferred. All that is now wanted (and paid for) is the ability to write feeble 'wisecracks ' for use on your lantern slides, to play a certain type of music in a certain way, and to exploit the resources of a modern unit organ with ingenuity and resource. Make no mistake: this is not easy. To many people it is impossible. A musical education is of little use: it may be actually a hindrance.

A natural feeling for crude rhythm, colour and harmony is the chief requisite, plus (if possible) an exterior like a film star and an unfailing confidence in your own superiority. This last qualification - technically known as 'a hard neck '-is well-nigh indispensable. Your procedure, then, is dubious. You may elect to take lessons from an established organist, and this is probably your wisest course. You had better 'listen in' a lot to the broadcasting organists. (You will probably be astounded at the sort of thing that passes for good playing.) The popular heroes appear to be strumming partly by ear and producing sounds which to the uninitiated have little connection with music. Never mind how inane it sounds; remember the great British public adores it.

But don 't delude yourself that you could do it: you couldn 't. It takes years of practice to produce just that particular brand of bad playing. Study good records, especially those of Quentin Maclean and Sidney Torch, which are first rate.

Listen to dance bands and imitate them on the organ: many of them do really clever work.

Remember that the staple fare in cinemas at present consists of dance music and sentimental ballads. If you can't play this sort of thing you have no chance of success.

The Organ

When you first approach a modern unit organ either of two things may happen: you may be completely nonplussed, or you may underestimate the task of managing one of these instruments.

True, it is quite easy to play 'straight' in a short time: one could, for instance, play almost at once a church service consisting of hymns, as is done in many cinemas on Sunday mornings.

The difficulty lies in really managing it and exploiting its possibilities in the particular style now in vogue.

This is where our F.R.C.O. is likely to come a cropper. He cannot grasp the essentials: there seems to be nothing to take hold of, and the sounds that can be produced by an expert seem unaccountable.

The Swell pedals now become all-important: pedalling is staccato and mezzo-staccato - indeed, this is more or less the staple touch throughout the organ: one even hears melodies played staccato. (I am not saying that this is good.)

One of the most extraordinary features of cinema playing, but one now falling into discredit, is the continuous use of the 'glissando.' Some organists use it incessantly. It is now on its last legs, so I will not dwell on it, but until quite recently it was looked upon as a 'hall-mark' of good playing in certain quarters. Used sparingly it can be effective on occasions, especially in dance music.

You will have to master double-touch, as this is a most important feature of the unit organ and greatly adds to one's resources.

The Vibrato (you probably call it the Tremulant) is also the rule and not the exception. Many hard things are said about cinema organists who over-use the vibrato, but unit-organ voicing makes it almost indispensable.

Accuracy is of the first importance: you 'orchestrate ' everything as you go ; in addition to your units you have at your command drums, cymbals, triangle, xylophone, chrysoglott, vibraphone, glockenspiel, chimes, and numerous other effects such as tambourine, wood block, &c., all of which are there to be used, and used frequently and judiciously.

The 'straight' organist will probably be puzzled by the pistons. There is very little 'build up' . instead there are groups of tone-colour; reeds alone; combinations of flutes ; strings and mixtures, and so on. Many organs have double-touch pistons, the second touch giving appropriate pedal stops.

We have just mentioned the 'units.' These are the essential feature. A complete unit consists of a rank of pipes (say Tibia) running from a 16-ft. C to the top C of a 2-ft. stop, or even less.

From this rank are drawn all Tibia stops on each manual and on the pedals. Thus a 16-ft. stop would come from the bottom pipe and five octaves up, a 2-ft. stop from the top five octaves, and so on.

If there are two manuals you might have Tibia 16-ft., 8-ft., 4-ft., 2-ft., 2 2/3, 1 3/5 on each manual, and on the pedals Quint, 10 2/3, 16-ft., 8-ft., 4-ft., 2-ft., seventeen stops in all off one unit. In a ten-unit job you might thus have a hundred and seventy stops: as a matter of fact not every available stop is used on each manual, but rather a selection.

The upper manual is called the Solo and is used as a Solo manual generally as well as a sort of Great organ. The lower manual is called the Accompaniment, and is a cross between a Swell, a Choir, and an Echo organ.

Owing to the fact that both manuals contain mostly the same stops the functions overlap considerably. A three-manual usually contains a 'Great' organ, but sometimes it is merely a dummy manual to which the others can be coupled either in unison or sub- and super-octave. This manual is much more useful than might be supposed.

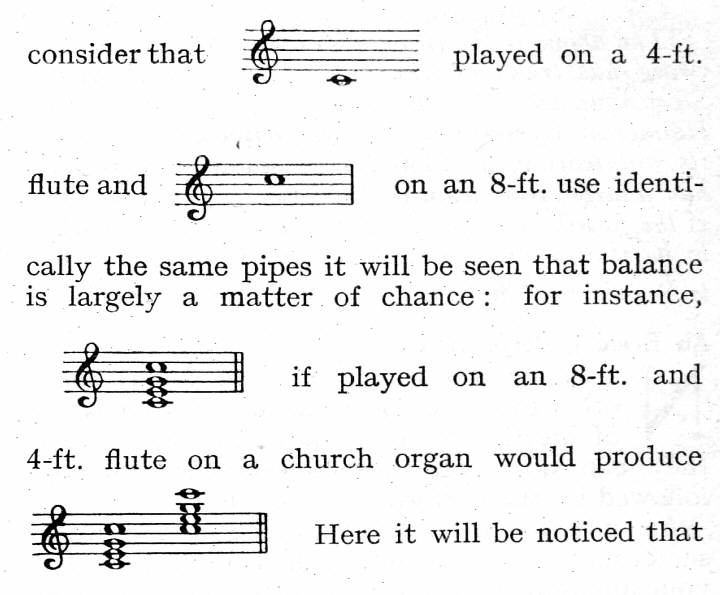

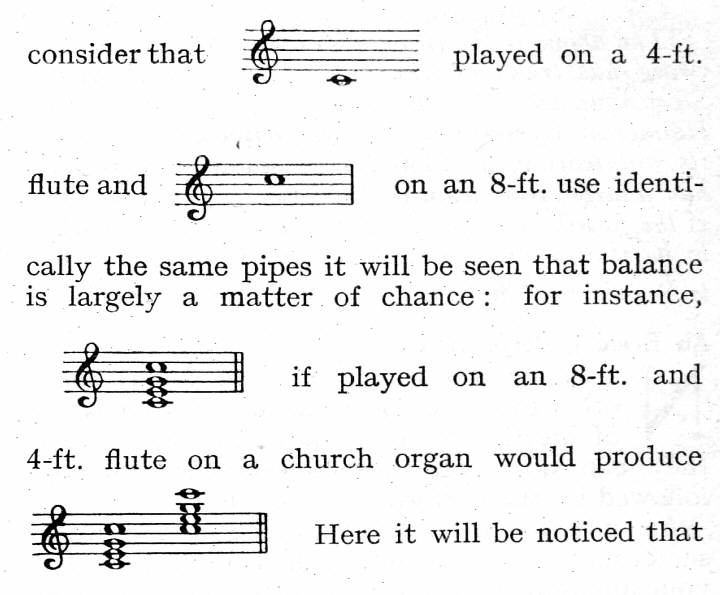

The Pedal organ is the weak part of a unit organ, as it usually contains only stops borrowed from the same units as the manuals, and it is therefore without the weight of a 'straight' organ. However, this certainly helps to keep the organ light and free from stodginess. When you

treble C is sounded by two different pipes and the upper or 4-ft.chord is weaker than the lower or 8-ft. chord: but on a unit organ not only would the centre C not be sounded by two pipes, but the 4-ft.

chord would be identically as strong as the 8-ft. chord: or, in other words, there is no difference between an 8-ft. and 4-ft. chord and the same chord on 16-ft. and 8-ft. played an octave higher.

Thus the sense of pitch is almost nullified.

It cannot fairly be said that the average 6-9 unit organ is a serious musical instrument. It is about on a par with the saxophone or piano-accordion. It has its uses and is capable of producing many fascinating effects, but the only thing it does really well is to produce a singing tone - and not every unit organ can do that. To play symphonic music on the cinema organ is to make it do what it cannot do really well; as for real organ music, the less said the better.

For some reason or other the 'lay out' of unit organs is too frequently cramped and uncomfortable, the seat being too high and not adjustable, the pedals too near in, and the manuals too low, so that pedalling is largely done under difficulties.

The music-stands are frequently too small and some are absurdly high; one organ on which I played had the bottom of the music-stand on a level with the top of my head. It is a tribute to the musicianship of the modern cinema organist that some unit organs have no music-stand !

Whereas in a 'straight' organ the diapasons are the groundwork and foundation, in a unit organ the foundation consists of the Tibia, Tuba, and Vox Humana. The last-named stop, however, seems to show signs of dying out, and as it frequently sounds like a goat in pain, 'it never will be missed.' At its best, however, it is a fine stop, especially in combination with a Tibia or strings.

There is frequently a diapason on a unit organ, but generally it is so small as to be merely an extra.

In the space at my disposal I can only indicate barely the lines on which to study a cinema organ. Practice and observation, plus some good lessons, must necessarily be the means by which the student acquires his knowledge.

Part II

If he is wise the aspirant will try to get into touch with one of the few unit organ builders, that being the only really reliable and reputable way now left of getting employment. The alternatives seem to be leaving it to chance or touting round the various circuits on the off-chance of someone someday answering one of your letters.

Some of the more shady resort to offers of underselling men already in work, and it is wonderful how the cupidity of some proprietors leads them to dismiss efficient players and engage 'duds' just in order to save two or three pounds a week. (Personal introductions carry a little weight.)

An American hair-cut and a pair of horn-rimmed spectacles have been known to work miracles, and a brief sojourn in the U.S.A. is an 'Open Sesame' to the hearts of the managing directors.

There is no space to tell of the peculiarities of these latter gentlemen - of how they invariably select the most obviously bad player for the most astounding reason, or dismiss you for no particular reason just before your summer holiday falls due, or tell you quite casually that from such and such a day you will also be manager and how nice that will be (at a reduced salary !).

A few firms are now springing up like mush rooms and offering salaries which would be inadequate for a dustman (though why so useful a person as a dustman should be paid less than a cinema organist I cannot say).

Some of these firms now engage a 'musical director,' usually some sort of musician, maybe an organist. This functionary receives a large salary, his chief duties being to intimidate the organists in his employ and keep the wages as low as possible. No likely rivals ever get work with that particular firm!

One of the biggest firms in the country employs lady ushers who also function as organists; they play the organ when not engaged in showing patrons to their seats. One such girl - an A.R.C.M. and L.R.A.M. - was paid £2 a week.

We will suppose that by good luck the reader is now in full possession of a real job and drawing a salary which may be anything from £2 to £20 per week, according to the amount of 'cheek' he possesses.

The first thing he should do is to master the organ he will have to play on; and he should not alter the combinations for a week or so. If he has a cinema organist friend he should get him to play while he himself observes the effects from different parts of the house. His duties will be all or some of the following:

(I) Open the performance with thirty minutes' recital.

(2) Join up.

(3) Stand by.

(4) Play Lights Up.

(5) Play an Interlude two or three times a day.

(6) Accompany variety acts.

(7) Play the National Anthem and a march out.

He will also have to 'get on' with the staff, and especially the manager: in fact, the church organist who substitutes 'manager' for' vicar, will find many points of resemblance, including the same childlike belief in their own musical judgment and the same conviction that the organist does not know what he is talking about. However, like the vicar, the manager is usually a very decent sort, and only requires politeness and consideration and some evidence that you can really do your work. You are expected to be punctual and thorough; no one tells you when to play or what to play-that is your responsibility. You are given a time-sheet and expected to be ready to 'do your stuff ' accordingly; if you are late and get told about it, remember to blame only one person - yourself.

Make a habit from the start of knowing what you are going to play throughout the day.

No matter how short the time (only a few seconds maybe), play something definite. Meandering, or so-called extemporizing, is even more deadly in a cinema than in a church (if possible), because all organists tend to become 'churchy' when extemporizing, whereas rhythmic music of a clear-cut nature is what is wanted in the cinema. Nothing can put a damper on a show so quickly as a succession of 'Amens' - which is what most improvising amounts to.

Have your programme ready for the recital. Find out the keys in which the various films start and end. Decide definitely what you are going to play at 'lights up' between the shows; and, above al], have some nice piece ready for accompanying 'silent' trailers and slides. Let your rule be 'No Extemporizing,' except in very rare circumstances.

Let us take the duties one by one:

1. Half-hour's recital. Here you have a chance to play something fairly good - selections, entractes, and so on. Start and end with some thing solid. A march makes a good start and an operatic selection a good conclusion. Play a few fox-trots, a waltz, and some light and attractive entractes. In other words, try to play what the average man likes.

Here are two programmes: (1) for a betterclass neighbourhood, and (2) for a slum cinema :

1. March, 'Lorraine ' … …Ganne

2. Short Selection of popular tunes of the moment

3. Selection, 'Lilac Time' ... … Schubert-Clutsam

4. Spanish Dance ... … Moszkowski

5. At the Ladybirds' Ball ... … Ewing

6. Selection, ' Faust ' ... ... Gounod-Tavan

II

1. March, 'On the Quarter-Deck ' ... … Alford

2. 'Melodious Memories' ... ... Finck

3. Waltzland … …Stoddon

4. Overture, 'Morning,.Noon and Night' … …Suppé

5. Ten minutes of Popular Songs, Past and Present

Your playing must be full of contrast - not loud all the time, as so many organists seem to think. You will find the audience will soon get used to your style, and you can tell by the applause which are favourite tunes.

2. 'Joining up' is the term used to describe modulating from one picture to the next. Here, if anywhere, is your chance for extemporizing. Finish the picture on the organ; make a conclusion; and then start at once working into the next picture. It is quite a test of musicianship. Sometimes one of the projectors is out of tune with the organ. This can and must be adjusted no matter what the operators may say

3. 'Standing by' is a sheer farce: It is just a survival from the days when talkies were first introduced. The sound used to fail, and the organist was expected to aggravate matters by playing the organ, thus letting the audience know that they were in for a long wait. 'Standing by' is now merely a device to prevent the organist from going out. No organist should agree to 'stand by' : it is an imposition.

4. 'Lights up' consists of playing a waltz, march, or other bright piece during the interval between the shows, usually only a few seconds. (Note. No extemporizing !)

5. 'Interludes.' We will deal with these in another article.

6. Accompanying variety Acts. This is an art : one of the few things a cinema organist has to do which he must do well. In effect he is now musical director, and must take all the responsibility. He should never be late nor waste time at rehearsals; he must insist on going thoroughly through all the music and cues; and, above all, he should make the tempi secure, especially for dancing acts. In the actual playing of a variety show a very crisp and bright style must be adopted, such as you hear from the best variety theatre orchestras. There must be no waits and no extemporizing.

While the stage is being prepared, play something quick, bright and rhythmic: not a waltz, but rather a few popular tunes on the quick side.

Don't keep the stage waiting when the green light shows; go into the music for the first act at once. Your only chance of changing the music from one act to the next is during the applause. Don't extemporize between the acts: it kills the show stone dead; always end each act so as to draw plenty of applause for the performers. It is possible to kill an act by a weak musical finish. Whatever happens, maintain the variety spirit to the very end.

Tap-dancing is about the hardest thing to play. Tempi are all-important; never lose rhythm in changing your stops. (In this respect, many church organists would benefit by a year's experience in playing for variety shows.) In accompanying singers keep down, but remember they mostly like you to play the melody and not merely the accompaniment.

Incidental music to conjurers, acrobats, etc., is fairly straightforward. It is useful to keep the side-drum roll on the second touch, for emphasizing tricks, somersaults, and so on.

Comedy acts usually consist of about two very much interrupted comic songs, a dance, and a lot of effects. This can be very difficult. If the performers don't say anything after the show the implication is that you have not been a success; they are generally most appreciative of good playing and are the first to praise you.

The hardest part about some acts is the remarkable scores you have to play from - amateur MSS., dogseared pages, leaves missing. sometimes only a flute part, and occasionally no part at all. You just have to do your best - and pretend to like it.

At any rate this branch of work certainly keeps you awake and is worth putting your best into.

The final article will describe 'Interludes.'

Part III

The Interlude

No matter how good a player an organist may be in other directions, he is judged finally by his ability to produce and play 'Interludes.'

The Interlude is a curious contrivance which has evolved gradually during the last few years.

It was found that people paid little attention to ordinary organ solos interpolated in the course of a picture programme, so someone hit upon the idea of 'staging' the organ solo and thus drawing attention and adding importance to it. The majority of people are unable to listen to music in vacuo - hence 'musical appreciation,' which consists largely in teaching people to associate music with concrete ideas.

Easily-understood music is after all only music which brings its own train of associated thoughts, sentimental recollections, or resemblances to other pieces which have their associated ideas.

Be this as it may, the Interlude is psychologically sound and therefore the idea caught on and continues to remain popular.

The console of the modern organ is ornate, and composed largely of glass lit from within by coloured lights under the control of the organist.

This decorating of the organ is somewhat malogous to the ornamental cases and screens so often seen in churches. In the majority of cases the console rises on a lift and a spotlight is directed on the organist.

The essential feature of an Interlude is that it shall take some subject as its text or motive. To concentrate attention on this subject slides are shown on the screen synchronizing with the music, and underlining and explaining it.

But unfortunately it is these same slides which have had such a demoralizing effect on our friends the cinema proprietors.

It has been found that 'wisecracks' on the screen have more audible effect on the audience, and draw more applause than the most attractive playing or the finest music. As a result the evolving of these slides is now looked upon as more important than executive skill or musicianship.

The question now put to the applicant for a position is not 'Are you a good player?' but 'Can you write funny interludes?' or 'Are you good at writing parodies?'

Much ingenuity is required to compose a weekly interlude year in and out, and the subject is a burning topic of discussion among cinema organists.

Let us consider the compilation of an Interlude as it might occur in the ordinary course of events. The manager may say merely, 'I want a twelve-minutes Interlude for the week beginning so-and-so,' or he may suggest a topic (which he is quite entitled to do).

Perhaps something appropriate to the film being shown that week is wanted; if there is a Russian film the Interlude could be on Russia and its music, and would in that case give the player a chance to show what he could do in selecting and playing some good examples.

Or again it may be New Year week, Christmas time, Derby Day, or what you will. If none of these things occur the organist must think of the best topic he can.

Interludes are nearly always composed of strings of tunes: very seldom is one single piece used throughout, except in pure exhibitions of playing; and in these instances slides are seldom used. (The organist who composes parodies for tunes is making a rod for his own back, as he will be expected to keep it up.)

Perhaps we have some tunes we wish to work in. Suppose we want to play' The Cricket's Serenade, because we think it is a nice little piece which we play well, suits the organ, and will prove popular.

We might then decide on an Interlude on animals: Title, 'A Day at the Zoo.' There are plenty of animal pieces suitable- 'The Penguins' Patrol,' 'The Glow-worms' Rendezvous,' 'The Lion' (March), 'The Tiger's Tail' (Americana), 'The Swan' (Saint-Saens), 'The Bees' Wedding,' 'The Butterfiy,' 'Golliwog's Cake Walk' (if you can call a golliwog an animal), 'Jumbo's Lullaby,' and of course 'The Cricket's Serenade,' concluding with the 'Monkey Blues' and 'Kitten on the Keys.' This would demand slides giving at least the titles of the pieces played and if possible some amusing comments.

Another simple Interlude might be called 'Dream Melodies,' and would include 'A Dream of Delight,' 'Liebestraum,' 'Traumerei,' 'Dreams' (Wagner), 'Dreams' (Gideon), 'The Miner's Dream of Home,' 'Dream Lover,' and end with 'When I grow too old to Dream' combined with vocal record on the 'non-synch.'

You can pick up ideas by reading the suggestions in each week's Kinematograph Weekly, but it is better to use these as a basis for your own Interludes rather than copy them as they stand, for the simple reason that the organist of the rival show round the corner may be playing the same one the same week as you.

Interludes based on operatic music prove popular, especially in neighbourhoods where there is a foreign element; but you had better stick mainly to Italian and French opera. Then, of course, Swing ("Swing" is a word fashionable at present, and denotes "jazz") Interludes are indispensable at times. By the way, Gilbert and Sullivan opera seems to be always a 'sure winner' with all audiences.

It is advisable to keep the musical part of the Interlude uppermost. Let the slides explain the music; do not let the music be merely an accompaniment to the slides.

Some organists speak to the audience instead of showing slides; but this calls for nerve and experience as well as a clear and audible delivery.

These remarks, of course, describe only the simple forms of Interlude. Some cinemas specialize in elaborate presentations with stage settings, moving film or Brenograph backgrounds for the slides, or loudspeakers to amplify announcements made either by the organist himself or by someone on the stage. Above all things, keep on friendly terms with the operating-box.

Its occupant can make or mar your Interlude, and may frequently suggest lighting and sound effects which would never occur to you.

Some organs instead of rising on a lift have a second console which runs out on to the stage for Interludes; duets could be played on the two consoles in the old days when two organists were the rule.

Any idea that occurs to you should be noted down; it may prove useful in the future. The simplest and one of the most popular Interludes is just a string of popular songs with the words thrown on the screen, so that the audience can do some community singing; and if you can once get them to sing they will enjoy this more than anything.

Soloists on the stage are occasionally heard in Interludes, but these usually steal all your thunder and bring the thing into the realm of a variety show or concert, with the organist as accompanist.

I have purposely made little reference to the most important subject of all: how to get a job when qualified. There is no one way of getting appointed. Most of the cinemas now belong to big circuits, and, if the organ-builders can do nothing for you, you should apply to the circuit supervisors or musical advisers, as the case may be.

As a last piece of advice let me reiterate: Unless you have no other prospect take Punch's advice - Don't.

-------------------------------------------

The series inspired the following response from a reader, which gives further insight into the subject-matter

Letters to the Editor - "The Musical Times", London, No. 1149 - Vol. 79, November, 1938, pp. 852-3

Cinema Organists : the Wobble, etc.

SIR, - The article in your September issue on cinema organ playing is very timely.

Looking at the matter from the standpoint of high art, the academic organist may be justified for the pained shudder with which he receives any mention of the work of his brother in the cinema. but let him not lightly suppose that it would be easy for him to change places, if circumstances compelled him to try it.

Mr. Chuckerbutty (who is known as a musician and organist of the highest qualifications) speaks with great authority and from experience, and his words are invaluable to would-be cinema organists, a class of aspirants all too numerous considering present-day prospects.

To the average church organist when inclined to sneer at the cinema player a little self-examination would not come amiss. He might ask 'Is my playing alive?' ; 'Can I touch the feelings of my hearers ?'; 'Am I an asset to my church ?'

When he can truthfully say 'Yes' to these questions, he may have a clear conscience; but until he can he is as much in a 'glass house' as his colleague of the cinema, who must have 'box-office value' to retain his post.

Having so far entirely agreed with Mr. Chuckerbutty, may I venture next to comment on his remark that unit organ voicing makes the use of the vibrato almost indispensable ? .

There is reason to believe that when the first unit organs were imported the makers recommended that the vibrato should be used all the time. This was probably a measure of self-protection, to conceal unsteadiness of wind with which they were sometimes troubled. However that may be, there is no doubt that the new type of instrument came before the public endowed with a perpetual wobble, which hearers came to take for granted.

Now if an organ is voiced with a view to continuous use of the vibrato (American for tremulant) it means a less meticulous standard of 'finishing'; and this is shown up if the vibrato is left off.

I cannot but think that the public taste was at the beginning perverted from this cause.

The English firm which has produced a large proportion of the cinema organs in the British Isles does not pursue this policy, and indeed provides (for example) that when the full organ is put on, the vibrato is taken off. [This is a reference to the practice on Compton organs whereby the tremulants were cancelled as soon as the General Crescendo pedal was used - IanMac]

I believe that the public was thus corrupted in the first place by purely commercial considerations. The circle is a very vicious one, but surely it can be broken. Cinema music is not bound to be as inartistic and cheap as it too often is.

In passing I consider that the perpetual use of 'background' music, both on the screen and in radio plays, is no less a degradation of the art.

Mr. Chuckerbutty represents the type of educated and artistic musician to whom we should look for rescue, and if a start is once made, we have brilliant men like Quentin Maclean (who, by the way. uses vibrato with the utmost artistry) to bring the king of instruments back from the (jazz)land of bondage.

- Yours, etc.,

F. HEDDON BOND.

Harrow.